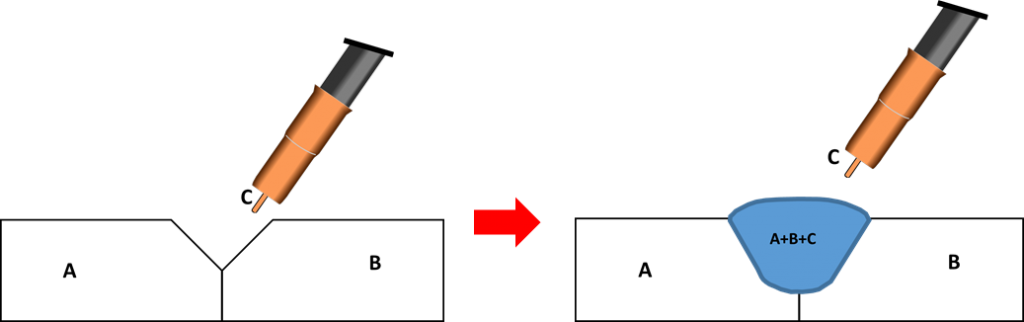

When we weld we generate enough heat in the welding arc to melt the filler metal and base material. Or just the base material is we are welding autogenously (as in GTAW without filler). The edges of the base material melt and combine with the filler metal to create what is called the composite zone. It’s called composite because it is a composition of the base material(s) and the filler metal as seen in the image below.

The heat affected zone (HAZ) is the area adjacent to the weld that was heated high enough to affect its microstructure but not enough to melt it. By undergoing microstructural changes the HAZ has different mechanical and physical properties than the weld and the adjacent base metal. These changes can be significant and even cause failure in the form of fracture, corrosion or other problems.

The base material and the thermal cycle (heating and cooling due to welding) as well as any post weld heat treatment (PWHT) are the determinant factors in how the HAZ changes. There are different potential issues with the HAZ depending on whether you are welding on mild steel, medium-to-high carbon steel, aluminum, stainless steel, or other base materials.

To explain the importance of the HAZ we’ll focus on carbon steel. The image below clearly shows the composite zone with the HAZ surrounding it. The HAZ is the darker shade around the weld and the unchanged base material is the lighter color adjacent to the HAZ.

The problem on steel is that if we have a rapid enough cooling rate martensite will form. Martensite is a hard and very brittle solid solution of carbon in iron. It is desirable in some cases because it is extremely hard, but at the same time may exhibit poor ductility. So it is good for tools, but not so great for structural steel.

The faster the cooling rate the more martensite will form. So to avoid, or at least reduce martensite, we need to slow the cooling rate. This is why we use preheat when welding on thick steel sections (regardless of carbon content) or with medium to high carbon steels (such as 4140 or 4340).

The danger of having a brittle HAZ in steel is the susceptibility for hydrogen induced cracking (HIC). This brittle microstructure fails under the pressure exerted by the hydrogen that diffuses out of a weld and HAZ. This is dangerous because unlike hot cracking which happens right after welding, most cold cracks (as in the case of hydrogen assisted cracking) do not occur until several hours after the part has cooled. This is why proper welding procedures call for inspection of welds susceptible to HIC 48 hours after welding is complete.

So with the HAZ being susceptible to all these problems it makes sense that minimizing it will only help. This is why post weld heat treatment (PWHT) is necessary on some steel weldments. And adequate PWHT will reheat a part that has been welded to a specific temperature to get rid of martensite and then cool at a very slow and controlled rate to avoid it from reforming, thus eventually cooling the part down to room temperature with no martensite to be found in the weld or HAZ.

Other alternatives are having welding procedures that minimize the HAZ. You can also use other processes that minimize it, such as laser welding. Welding with laser produces an extremely small HAZ thus reducing the problems associated with the HAZ.

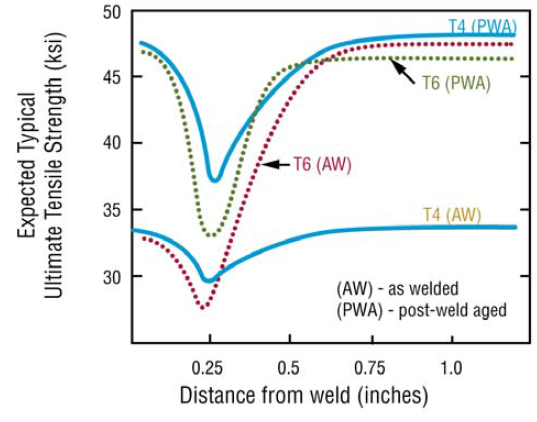

Other types of base metals, such as aluminum, have their own set of challenges. In aluminum welds the heat affected zone is always the weakest area of the weld. The image below shows the tensile strength of the base aluminum away from the weld. As you can see the strength drops as we get into the HAZ and then comes back up when we are back in the pure, unaffected base material.

This is the opposite than in steel, where the HAZ can become extremely hard and has very high tensile strength. Opposite conditions, but neither is necessarily desirable. Having a clear understanding of the base material you are welding and how the heat input, cooling rate and other important factors affect the HAZ is crucial in avoiding failure.

References:

Welding Procedure Development for Non-Welding Engineers (2021)

Metals and How to Weld Them – Theodore Jefferson, Gorham Woods

Nice explanation….Good work!