Many fabricators can lower their welding costs significantly if they paid close attention to weld sizes. If a print calls for a ¼” fillet weld and in production you make a 5/16” fillet weld, you are overwelding by 56%! If the print calls for a 3/16” fillet, the 5/16” fillet weld you deposit would be overwelding by 177%, or almost three times the required amount.

If we have prints that call out weld sizes then overwelding is relatively easy to solve. Provide training for welders and give them the right tools so they can deposit the weld sizes stated in the print. However, if we don’t have weld sizes specified on our prints and we are forcing the welders to determine weld size on their own, we are opening up the door for trouble. Not just to potential quality issues but to a tremendous increase in welding costs.

There is a Rule of Thumb for fillet weld sizes that you have probably heard…

“Fillet welds should be ¾ of the thickness of the material being weld.”

So does this mean that if we have a ½” plate we should put down at ½ x ¾ = ⅜” fillet weld?

First let’s go through a few items regarding this rule of thumb.

- The rule of thumb assumes you need to achieve full strength. This means that exceeding the size specified would increase weld strength, but not the connection strength. Meaning welding anything bigger would be total waste with no added benefits.

- The weld is on both sides of the joint. The rule of thumb assumes a double-sided fillet weld.

- Both legs of the fillet weld are of identical size.

- The weld is made for the entire length of the joint. The weld cannot be intermittent or less than full length. This applies for both sides.

- When the members being joined differ in thickness the thinner member must be used for this calculation.

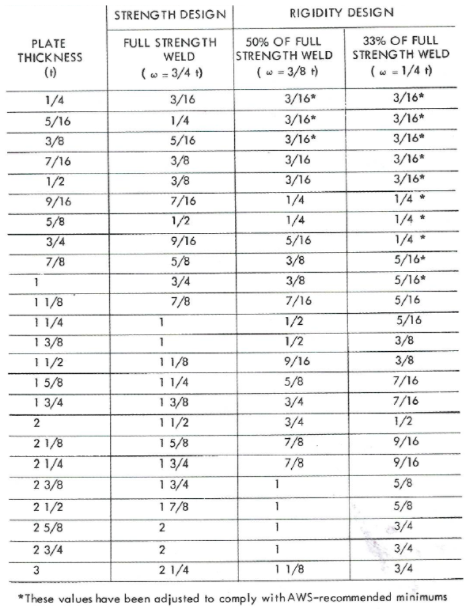

In the absence of a qualified design engineer to determine weld sizes we can at least make sure we do not exceed the size that will give us full strength. Below you can see Table 1 from Section 6.3 of Design of Weldments by Omer Blodgett. It shows the size of the fillet weld to achieve full strength, 50% strength and 33% strength.

Take a look at the note at the bottom of the table. This makes reference to the fact that AWS D1.1 Structural Welding Code – Steel specifies minimum sizes for fillet welds. This is because if we determine fillet weld sizes based on the actual loads experienced by the weld we may end up specifying weld sizes that are too small and could lead to cracking. This cracking is not due to lack of strength, but rather due to hydrogen induced cracking. Minimum weld sizes are specified in order to have enough heat input to prevent a cooling of the weld and heat affected zone that is too rapid and which may cause embrittlement.

More often than not, design engineers that understand how to size welds properly, take advantage of using minimum weld size, not sizes that provide full strength.

In many cases, where we don’t have any design expertise, what we are looking for is to not exceed the needed weld size for full strength. So let’s consider the following example.

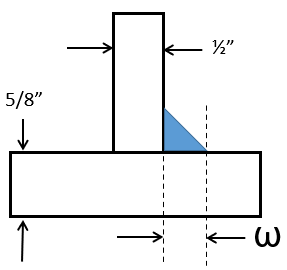

EXAMPLE: A T-joint is made up of two members and is 12 inches in length. Both plates being joined are ASTM A36 material. One plate is ⅝” thick and the other ½”. The joint is to be welded from both sides and for the entire length of the joint. What size weld should you put down if you have no information regarding the loads acting upon the weldment in service?

ANSWER: Following the rule of thumb: Fillet weld leg size must be equal to ¾ x ½ = ⅜” leg size. We use the thinner member (½ inch), not the thickest (⅝ inch).

The next step would be to consider making the fillet weld smaller, but that will require some engineering assistance or at least an understanding of loading conditions. In this case we could potentially make the fillet weld as small as 3/16” based on the minimums specified by the American Welding Society.

This would represent a reduction in weld volume of 75% (going from a ⅜” to a 3/16” fillet weld leg size). On a single weld this may not be a concern. But if you consider all the welding done in a year this could be costing you thousands of dollars.

Reference: Design of Weldments, Omer Blodgett

glad to receive the publication after a long time.

Yes, this year was tough. BUt we are all geared up to publish weekly again next year.

This statement is false and would greatly reduce the strength required in individual aspects of welding where a 3/8″ base plate is welded to 1/4″ carcass, anything less than a 1/4″ fillet weld would be deemed as insufficient

Thanks for the note Chris, but can you please be more specific? Why do you believe a 3/16″ fillet weld would be insufficient if welded full length from both sides joining 1/4″ to 3/8″?