Our last post (Factors Influencing Hydrogen Induced Cracking) went over the factors that contribute to hydrogen-induced cracking. We will now go over how to prevent HIC from happening. If you recall, we mentioned you need all three factors to be present in order to have HIC: These factors are 1. a susceptible microstructure, 2. threshold level of hydrogen, and 3. high restraint levels. So let’s see how we can eliminate at least one of these factors…

Susceptible Microstructure

A susceptible microstructure is the product of two things: base metal composition and the thermal cycle induced by welding. We may not always be able to change the base material, but we should be able to significantly affect the thermal cycle induced by welding. In order to prevent a microstructure that is susceptible to HIC we need avoid the formation of martensite. Martensite is very hard and brittle. Martensite will form when we have rapid cooling in steel.

The final microstructure of a weld and the HAZ is a product of the base metal composition and the thermal cycle induced by welding.

To avoid rapid cooling we need to preheat the base material. To learn more about why preheating you can read: Why Is Preheating Necessary. By bringing the base material to a certain preheat temperature the weld and heat affected zone will take much longer to go back down to room temperature and thus reducing or elimination the formation of martensite. The use of thermal blankets to further slow down the cooling rate is also helpful. Lastly, using post weld heat treatment to “bake out” the hydrogen is also an option.

Threshold Level of Hydrogen

From our last post we know that most materials contain traces of hydrogen, but the hydrogen associated with HIC is a product of the welding process. This hydrogen is introduced into the weld due to: moisture in the electrode, flux, shielding gas or environment and contaminants containing hydrogen such as grease, oil, and cutting fluids.

In order to eliminate these sources of hydrogen we implement low-hydrogen practices which include:

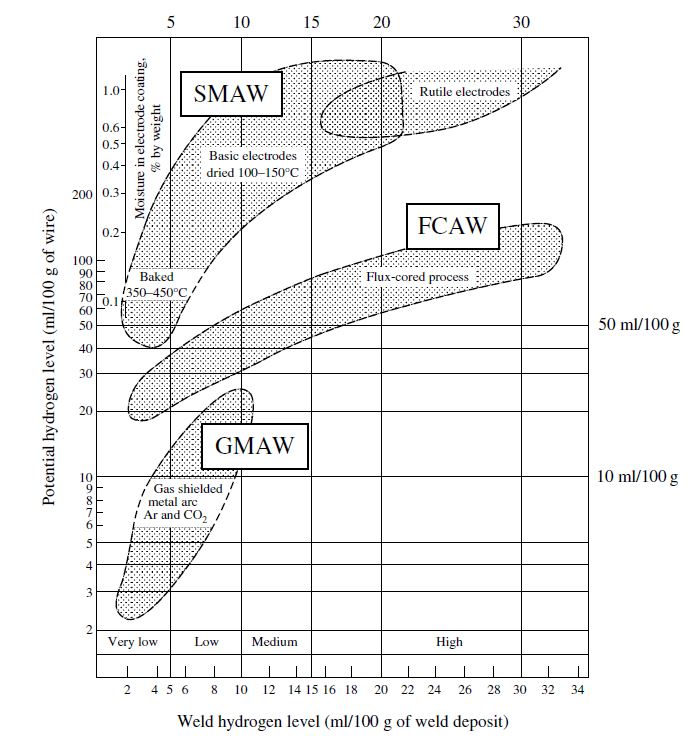

- Use a low hydrogen process (GMAW and GTAW are best due to not having flux that can pick up moisture)

- If SMAW is to be used make sure to use low-hydrogen rods such as E7018.

- With processes involving flux make sure consumables are stored properly. In the case of opened cans of stick electrode these should be kept in a holding oven at the temperature specified by the manufacturer.

- Clean the base material, especially the edges to be welded

- Proper control of preheat and interpass temperature.

Effect of process selection in susceptibility to HIC.

(Ref. Bailey N, Coe FR, Gooch TG, Hart PHM, Jenkins N, Pargeter RJ. Welding Steels without

Hydrogen Cracking. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 1993)

Restraint

The level of restraint is typically hard to change. The restraint will be come from shrinkage resulting from solidification, thermal contraction and external forces such as fixtures, clamps and the sheer size of the components being welded. As you can image it is hard to do away with these. You can control residual stresses with proper post weld heat treatment, but some parts are too massive to fit in a furnace. You may be able to change your welding process to avoid excessive heat input but it may not be practical or economical.

Avoiding stress concentrations due to welding is critical. This means make sure you have no weld discontinuities such as undercut, excessive reinforcement, concave face, overlap, etc.

Source: Welding Metallurgy and Weldability by John C. Lippold

Please note: I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive or off-topic.