In our previous two articles we talked about categorizing cracks based on when they occur and in which direction they propagate. Today on our third and final article on understanding why your welds crack we look at the importance of location.

If you want to review or if you missed our previous two articles simply go to Understanding Why Welds Crack: Timing and/or Understanding Why Welds Crack: Direction.

For review, here are the three ways we must categorize cracks when doing failure analysis.

- Timing – did the crack occur immediately after welding (hot crack), did occur after the weld and base metal cooled down (cold crack), or did occur days, weeks or months later while in service.

- Direction – is the crack longitudinal or transverse?

- Location – where did the crack occur (i.e. root, toe, centerline, underbead, etc.)?

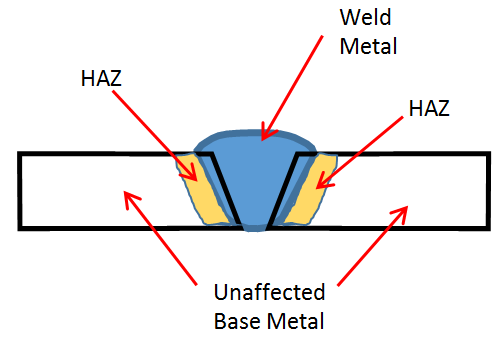

The location of the crack is very important as it can provide a lot of information regarding its root cause. There are many types and names for cracks based on their location. To keep things simple we are mainly concerned with only three areas in which cracks occur: weld metal, heat affected zone and unaffected base metal.

Cracks can be categorized by their location: weld metal, heat affected zone and unaffected (by heat) base metal.

Let’s look at the types of cracks that can occur on each of these zones.

Unaffected Base Metal

Lamellar Cracks – these types of cracks are also called lamellar tearing and occur in the base metal away from the heat affected zone in the unaffected base metal. These cracks occur when the shrinkage stresses are perpendicular to the faces of the plate which have been rolled. It is driven by sulfur inclusions in the base material. In some cases the tear can occur in the HAZ. To prevent this, the amount of sulfur in steel must be kept below 0.005%. Better joint design can also help prevent this issue.

Lamellar tearing or cracking occurs as a result of sulfur inclusion in the base metal and shrinkage stresses introduced by welding.

Heat Affected Zone

Heat Affected Zone Cracks – Cracks in the HAZ can be longitudinal or transverse. Most the crack in the HAZ are cold cracks or hydrogen induced cracks. Cracks in this area typically the result of excess hydrogen, inadequate preheat heat, inadequate maintenance of interpass temperature, cooling rate that is too fast, highly restrained joints, or a combination of two or more of these factors.

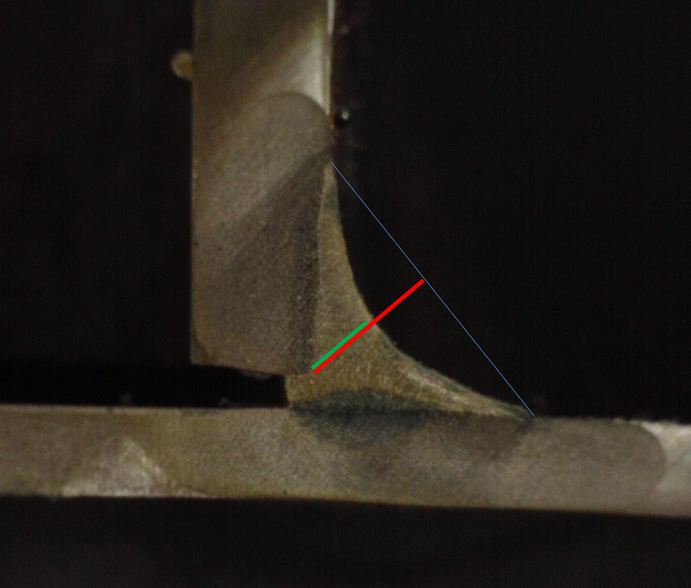

HAZ cracks will be very close to the fusion line but occur in the base metal, not the weld metal. Depending on their location relative to the weld, the cracks are also known as underbead cracks, toe cracks or heat affected zone cracks.

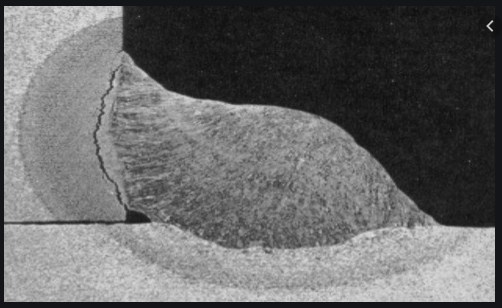

Heat affected zone crack induced by hydrogen. The crack originates at point of high stress as hydrogen diffuses out of the weld and heat affected zone.

We have been referencing information on hydrogen induced cracking in the past few articles. When dealing with steel, cracks in the HAZ are typically the result of hydrogen induced cracking. This means that three conditions are present: a sensitive base metal microstructure, a highly restrained joint (a threshold level of restraint) and a source of hydrogen. To alleviate HAZ cracks use low-hydrogen practice. It is at times difficult, if not impossible to change the level of restraint or the base material, so eliminating or greatly reducing the source of hydrogen is usually the only option.

Weld Metal Zone

A large portion of cracks that occur in welding will be in or through the weld metal. Most of these cracks occur when the weld metal is still above 400˚F [205˚C] and are thus called “hot cracks.”

Crater cracks – these cracks occur at the end of a weld where the full cross section of the intended weld is not achieved. A crater is left behind. As the weld metal shrinks there is insufficient weld metal to resist the pulling form the base metal and cracks developed. This problem is very common in aluminum, but can also occur in steel. To fix this issue simply fill the crater. You can use a back stepping technique or use the crater fill option on some of the newer power sources. Filling the crater must be done without extinguishing the arc or no more than a second or two after doing so. If you allow the weld to completely solidify and the crater to form you may not get rid of cracks by welding over it.

Craters at weld terminations are very common in aluminum and can lead to solidification cracks. These can also occur in carbon steel.

Centerline Cracks – these cracks occur due to the presence of low melting point elements in the weld metal such as sulfur, lead, phosphorus, zinc and copper amongst others. The crack occurs longitudinally along the weld and is also called a solidification crack. To avoid this issue, filler metals with low levels of the above mentioned elements must be used. This problem can also occur due to pick up of these elements from the base metal due to high admixture.

Top view of a centerline crack. Sometimes these cracks are barely visible to the naked eye and thus non-destructive inspection methods like liquid dye penetrant are used.

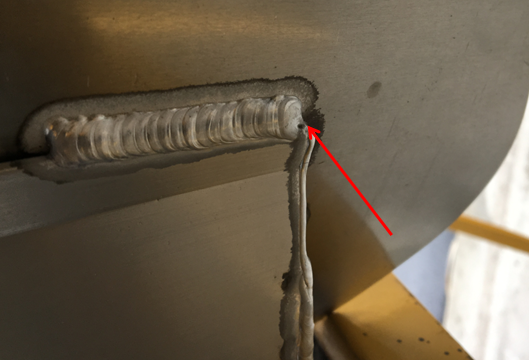

Throat Cracks – these cracks occur along the throat of a weld. They can be centerline cracks that develop during solidification, but can also occur in service after applied loads cause the weld to fail along its throat. This is a perfect example of the need to know the timing of the crack, the location and the direction. If you have centerline cracking which is longitudinal, and occurs immediately after welding, we know it is due to segregation of low melting point elements. However, if it occurs several days later when the weldment is in service we can start looking at other causes such as overload. Other issues may be welding defects that went undetected such as excessive concavity, lack of root fusion, lack of penetration, etc.

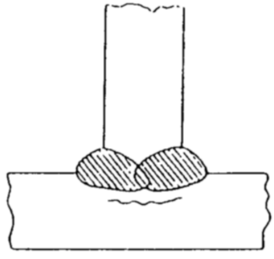

Concave welds reduce the dimension of the throat. The strength of the weld is directly proportional to the effective throat. When the throat is too small the weld may not be able to handle in service loads and will crack along the throat (green line).

Root Cracks – these cracks originate at the root of the weld. They can manifest themselves as throat cracks or propagate in other directions. They are caused by weld imperfections at the root. Slag inclusions are usually the culprit; however, as is the case for throat cracks, lack of root fusion can also cause root cracks. The image shown for heat affected zone crack is also an example of a root crack due to the point of origination.

There are many other names for cracks based on location. The key is to identify where the crack started: in the unaffected base metal, in the heat affected zone or in the weld. Then combined with the timing and the direction you can easily narrow down the possible causes and correct the issue.

References:

Steel Design Guide 21: Welded Connections – A Primer for Engineers

Welding Metallurgy and Weldability by John C. Lippold

Please note: I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive or off-topic.